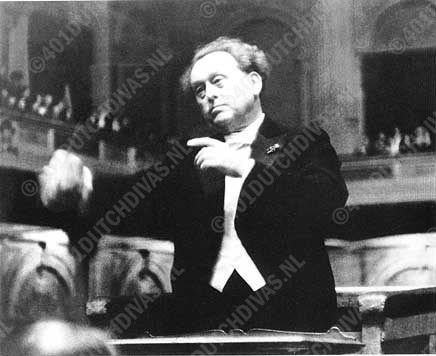

Willem Mengelberg Biograhy, part two

NATIONAL HERO

During the years in which Mengelberg conducted the Concertgebouw Orchestra his popularity grew to such an extent that he occupied the position of a national hero, perhaps best compared today with the positions of film stars and sports idols. He gradually came to belong to the category of 'well-known Dutchmen'. Mengelberg was news and his triumphs in foreign countries were usually broadly publicised in the national press. Even when the famous man was ill or suffered some minor accident, had his birthday or some anniversary, his name was in the papers. Many an opportunity was taken to celebrate him and numerous honours and presents were showered on him: wreaths, beautiful albums written in calligraphy and even a car were given to him. The supreme moment was of course the overwhelming honour paid to him at the Mahler Festival in 1920, but even then there were many impressive celebrations to come.

Mengelberg was swamped with honours and decorations. In The Netherlands he received the following decorations: 1898 Knight of the Order of Oranje Nassau, 1902 Officer of the Order of Oranje Nassau, 1907 Knight of the Order of the Dutch Lion, 1907 Silver Medal for Arts and Sciences in the House Order of Oranje Nassau, 1913 Gold Medal for Arts and Sciences in the House Order of Oranje Nassau, 1920 Commander in the Order of Oranje Nassau, 1934 Grand Officer in the Order of Oranje Nassau. He could call himself Professor Mengelberg after being made extraordinary professor of musicology at the State University of Utrecht, in 1934. A few years before that he had already been given an honorary doctorate at the University of Columbia in New York. In the same period he received royal and governmental decorations in Belgium, France, Italy, Spain and Denmark. Academic institutions and all sorts of musical societies gave him honorary membership or an honorary position. Mengelberg's portrait was painted by such well-known artists of the day as Pier Pander, Jan Toorop, Jan Sluijters and Kees van Dongen.

Mengelberg's fame rested on his musical genius as it was expressed in his performances, many of which were recorded for posterity. One of the monuments which contributed to his fame was the yearly performance of the St. Matthew Passion by J.S. Bach. It is a pity that there is no earlier recording than the one made in 1939. There are some other distressing gaps in the rich phonographic inheritance from Mengelberg. The music of Mahler is by no means fully represented in recordings and it is particularly sad that there is no record of 'Das Lied von der Erde', the work which achieved singular perfection in the hands of Mengelberg, with Ilona Durigo and Jacques Urlus singing as the soloists in Mengelberg's performances for many seasons. It was with 'Das Lied von der Erde' that Mengelberg made his successful first appearance in Vienna in two performances with the Vienna Philharmonic. At the first concert, given on the 30th December 1917, the fanatically applauded performance was rewarded by a generous gift from Alma Mahler. This consisted of two manuscripts of 'Der Abschied' from 'Das Lied von der Erde', one of a preliminary version and one in full score, with the following flattering dedication:

Willem Mengelberg and Marianne Günther,who looked after him during his concert journeys, 1934

"To the Friend of Gustav Mahler

The most wonderful interpreter of his work Willem Mengelberg [. .] Given by Alma Maria on the 30th Dec.1917".

At the second concert with the Vienna Philharmonic, given on New Year's Day 1918, Mengelberg conducted Mahler's Fourth Symphony and Ein Heldenleben by Strauss.

At the end of the thirties and before he became professor, the Amsterdam musicologist Bernet Kempers made a plea to the Dutch government to give financial support to make a recording of Mengelberg's interpretation of 'Das Lied von der Erde'. Sadly, this project was never to be realised.

THE YEARS 1940-1945

On the 'Zuider Sea', March 1906, standing from left to right: Alphons Diepenbrock, Gustav Mahler and W. Mengelberg.

Sitting: Mrs. Mengelberg, Mrs. H.G. de Booy-Boissevain, Mrs. P.J.Boissevain and Mrs. M.B. Boissevain-Pijnappel.

The most controversial and often discussed part of Mengelberg's career is the period between 1940 and 1945. A number of publications which came out shortly after the German invasion of The Netherlands in 1940 ensured that Mengelberg's unrivalled popularity disappeared for good for a large part of the Dutch nation. It was especially the article which appeared in the newspaper 'De Telegraaf' on the 10th of July 1940 which compromised Mengelberg. It was a version of an interview which had appeared in the the 'Völkischer Beobachter', the German national-socialist paper, on the 5th of July. The version published in De Telegraaf was commented upon with indignation in the Dutch press.

Whoever saw the photo series made by Mauritius Hartmann in Berlin in 1940, and which was partly published in the German magazine Der Silberspiegel, would again have had reason to turn his back on Mengelberg. On one of the photos Mengelberg and his wife, both smiling, are looking at a poster on which his concert of the 5th of July 1940 with the Berlin Philharmonic is advertised. On other photos Mengelberg can be seen as a tourist in Berlin. On his return from Berlin, Mengelberg gave an interview to De Telegraaf which appeared on the 2nd of August 1940. Mengelberg's damaged reputation was certainly not improved by this interview. The contrary was the case. The final remark ran as follows:

"I shall stay for a while in The Netherlands to have some discussions about Dutch musical life and hope to do some useful work to continue its improvement." Other remarks also gave, and still give, an uncomfortable feeling.

Willem Mengelberg with his wife - Tilly Mengelberg - in Berlin, July 1940

The reputation of Mengelberg was also not improved by photos of him together with such men as state commissioner A. Seyss-Inquart or NVV leader Woudenberg, taken on special occasions. Whether or not it was true, many people were given the impression that Mengelberg was in an animated conversation with this company.

The programmes for the music which Mengelberg conducted during the war show that he not only continued with his concerts in The Netherlands but also carried on as guest conductor in other countries occupied by the Germans and in Germany itself. Famous soloists were often at his side such as the singer Henriëtte Sala, the pianists Branka Musulin, Dinu Lipatti, Soulima Stravinsky (the son of Igor Stravinsky), the cellist Paul Tortelier and the violinist Willi (probably Wolfgang *) Schneiderhan. Mengelberg's justification for his concerts in Germany and elsewhere lay in his principle, which he had openly expressed, that just as the sun shone indiscriminately for everyone, so too was music made for all people. Nonetheless, the music on the repertoire gradually became thinned down. On the 5th of July 1940 Mengelberg could give a 'Special Concert' of music by Tchaikowsky to celebrate the one hundredth anniversary of the birth of the composer. Then, Mengelberg could also make recordings of Tchaikowskv's music for the German company Telefunken. But in February 1944 special permission had to be asked from the state commissioner 'Reichskommissar' - the highest authority, in order to give a couple of performances of Tchaikowsky's music. He was, after all, an 'enemy' composer.

*) the critics a few days later in the Pariser Zeitung by Dr. Heinrich Strobel shows no doubt that it handles indeed about Wolfgang. J.L.

"Ik blijf nu eenigen tijd in Nederland om besprekingen te voeren betreffende het Nederlandsche muziekleven en ik hoop nuttig werk te kunnen doen voor de verderen opbouw ervan."

*) Het programma vrmeldde inderdaad Willi, maar de kritiek die enkele dagen later in de Pariser Zeitung van de hand van Dr.Heinrich Strobel laat er geen twijfel over bestaan dat het om Wolfgang ging. J.L.

Mengelberg with his dog Rin, April 1947

Mengelberg is often described as a man of boundless naiveté in order to explain and to play down his position in the Second World War. But it must sadly be admitted that this naiveté was effectively bad. It allowed Mengelberg to ignore political significance and to continue his work as a musician unabated. This in turn allowed the Germans to use him for their propaganda. It was perhaps the

same borderless naiveté which led him to put music by Mahler on his programmes in the Autumn of 1940. The music of his friend Gustav Mahler, as a Jewish composer, was forbidden. The 'Reichskommissar' became annoyed on hearing of Mengelberg's unthinking intention to perform works by Mahler. But as a special exception, one work by him was allowed and Mahler's Symphony No.1 was heard again.

The same naiveté which led him to approach the German authorities in The Netherlands on behalf of many people, Jewish and otherwise. These included the violinist Carl Flesch, the flutist Hubert Bahrwahser, Prof. E. Laqueur, the pianist Sara Bosmans-Benedicts and many others. Whoever came to Mengelberg could count on his mediation. But the requests for help do not appear to have shaken him into awareness.

It is an extraordinary paradox that the man who had fought so hard to persuade not only musicians but also the national and international public of the importance of the music of Mahler should later acquiesce in the prejudice of a tyrant. Mengelberg somehow did not allow himself to see that the sun did not shine for everyone, that even musicians, composers and their work were forced into a scheme of things which placed no value on freedom.

It cannot be doubted that the findings of the Honorary Council for music in 1945 and the Central Honorary Council for Art in 1947 to a large extent determined feelings about Mengelberg during his exile in Switzerland. For his attitude during the occupation the council of 1945 imposed a sentence which forbade him to ever conduct in The Netherlands again.

Mengelberg's defence in 1945 and his appeal in 1947, both presented by his lawyer J.A.J. Bottenheim, the son of Mengelberg's former secretary S.A.M. Bottenheim, demanded a lengthy and thought-provoking process. Much attention was paid to whether Mengelberg should be given the necessary documents to travel outside Switzerland, for instance to The Netherlands. Mengelberg was plagued by sickness and was often physically weak. The withdrawal of the royal decoration, 'The Honorary Gold Medal for the Arts and Sciences in the Order of the House of Orange' by royal decree on the 19th of March 1947 must have caused Mengelberg considerable distress at his home in Switzerland, especially then when there appeared to be some hope that his sentence might be completely revoked or at least changed. This distress was increased by the decision of the Central Honorary Council. The appeal case, which was opened before the Central Honorary Council in May 1947, ended on the 20th of October 1947 with a reduction of Mengelberg's sentence from a life-time ban to one of six years, until 1951.

Until his death in 1951, Mengelberg remained in his chalet in Switzerland. Apparently, his friends were unable to successfully make clear to him exactly what had gone wrong and the reasons for all the radical measures and decisions. His feeling of being misunderstood is expressed in his own words: "I have never done anything wrong against my country, was always and still am a loyal subject of Her Majesty.

[.. .] Everything I did and did not do during almost fifty years of working in The Netherlands including the war period was directly or indirectly for and on behalf of my country, Amsterdam and the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Thinking that this was sufficiently understood [.. .] made the shock at discovering that the opposite was thought of me deeper still".

In 1946 his astounding naiveté was still apparent in words he wrote to Ellie Bysterus Heemskerk: "If I had done something I could understand it, but I never got involved in anything!...".

Frits Zwart

........Newspaper-report, 5 September 2001, Ricardo Chailly, chief-conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra puts flowers on the grave of his predecessor Willem Mengelberg. His artistry comes at present more to be in the foreground......